“There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen.”

How have the Isle of Man and other small states responded to those recent COVID-19 related weeks?

The Isle of Man is an island of around 85,000 people and 227 square miles, located in the Irish Sea roughly midway between England, Scotland and Ireland. It is a Crown Dependency and not part of the United Kingdom; rather it is a self-governing possession of the British Crown, responsible for all its own taxation, spending and policy decisions, with the United Kingdom responsible only for its defense, international relations and overall “good government.”

It has a diverse economy, spanning banking, insurance, trust and fiduciary services, e-gaming, media, manufacturing, food and drink production and tourism. In the last 35 years, it has only had one year without positive economic growth.

It is also home to the Small Countries Financial Management Centre (SCFMC), a charity set up in 2009, whose purpose is to contribute to the growth and prosperity of small developing countries through capacity building at senior official levels in the government financial sector. The SCFMC achieves this through the provision of targeted executive education programmes conducted by practitioners and academics to provide improved skills, deeper understanding and best practice around financial regulation, risk management and broader management of government financial activities.

The SCFMC meets all the costs of the Programme, including travel and accommodation for participants. Since its inception, 267 senior officials from 31 small countries have participated in its annual Small Countries Financial Management Programme. The SCFMC receives the majority of its funding through the Isle of Man Government’s development aid budget. As with the rest of the world, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought the most extreme challenge to the Government and community of the Isle of Man.

Initially, Government’s first priority was the preservation of life. Its initial strategy prioritized this, along with the maintenance of crucial national infrastructure, maintenance of public safety and confidence and supporting a controlled return to normality.

Whilst hindsight might suggest the actions associated with the “Stay at Home” stage, particularly relating to the closing of the Island’s borders on March 25th might have been implemented a little earlier, the raft of measures taken by the Government has succeeded in limiting the spread of the virus on the Island.

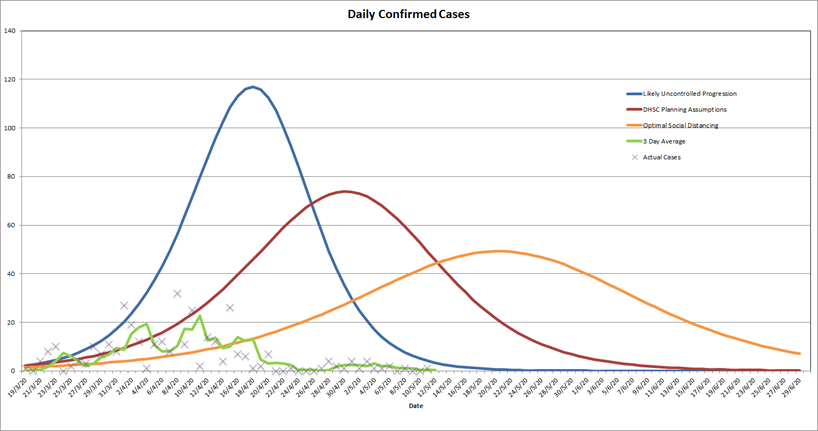

Its success in “flattening the curve” is illustrated by the following graph.

However, the Island has seen unemployment rise dramatically from 461 to 850 (2% unemployment rate) between February and March, with further increase seen as inevitable in the forthcoming months.

To mitigate the impact of its lockdown measures on both individuals and business, the Government introduced a range of measures estimated to be costing the Government £100 million for the first 12 weeks’ support, being drawn from reserves built up over the last 40 years.

The ability to “pull up the draw bridge” and close borders more easily than elsewhere can be advantageous in the initial phase. But coming out of that phase to re-introduce local economic activity and, crucially, to attract new business opportunities to supplement or replace those damaged by the lockdown is the most difficult of policy and political judgements.

As with all other small states, the Island is concerned with actions necessary to position its economy to survive and prosper in the “new normal.”

Moving onto the responses of the small countries which have participated in the SCFMC’s annual Programmes, whilst varying in detail, these responses have been broadly similar to the Isle of Man and indeed most responsible countries, with declarations of Emergency Powers, social distancing, border closures and quarantine periods of at least 14 days, lock-down or curfews of varying restrictiveness and duration, closure of schools, shops, with varying severity, restrictions on social gatherings and home working where possible. Many have introduced fines of varying levels -some draconian- for regulation breaches.

Some SCFMC countries, particularly those in the Pacific such as Samoa, Vanuatu, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu and the Cook Islands, have no confirmed COVID-19 cases, although the economic impacts are being felt severely, particularly with the collapse of tourism and reduced remittances. For example, in Samoa, tourism is reported to provide 12% of employment and poverty has “surged.”

Many other SCFMC countries’ economies, including those in the Caribbean, are also highly tourist-dependent and are suffering severe economic strain. With tourism closed, their governments face exceptionally challenging times with revenues having plummeted even as COVID-19-related expenditures have increased dramatically.

Mr. Timothy Antoine, Governor of the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank (ECCB), a SCFMC alumnus, recently suggested that the Bank’s COVID-19 impact scenarios had suggested economic activity in the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union (ECCU) area as projected to contract between 5.0 per cent and 7.0 percent (in real terms) in 2020, accompanied by a sharp rise in unemployment. This compared to a pre-pandemic economic growth projection of 3.3 per cent.

In response to these economic pressures, most small countries have brought in relief packages for businesses and individuals. For example, Samoa passed a US$23.6 million relief package to help the country’s hotel sector, which had been forced to layoff 500 hotel workers.

The Bretton Woods organizations have been called upon for assistance. For example, the IMF has provided Emergency Financing Relief from its Rapid Credit Facility (RCF) to seven SCFMC countries, ranging from US$14 million to Dominica to US$31.23 million to the Seychelles.

Nevertheless, as in the words of Governor Antoine, we move from “saving lives to saving livelihoods and economies.” There are some key areas the Isle of Man, along with all other small Island states, need to address and resolve quickly.

Opening up after lockdown will not simply lead to previous economic activity returning. For example, countries dependent on tourism will find it very challenging, both in terms of building confidence in prospective visitors and in the resident population’s willingness to accept the risks of re-introduction of the virus.

The international environment for small countries will be harsher than ever before. Larger countries will be more inward looking, with protectionism more to the fore. All countries will be even more merciless in protecting existing business and attracting new business.

The interests and impact on smaller countries will be of even less interest to larger countries than previously, and there will be early and intense pressure exerted in taxation and regulatory areas, with little or no regard being paid to assisting smaller nations in developing alternative economic opportunities.

Taxation and regulatory regimes will need to be redesigned to withstand international criticism, whilst remaining internationally competitive.

The maintenance and development of a business environment conducive to the attraction of new business will be of fundamental importance, as will the abilities of small countries’ governments to be flexible, swift acting and focused in delivering such environments.

This will involve governments addressing rigorously, both at a political and official level, how they think and act, and balance the needs and aspirations of their populations with those of the businesses they need to retain and attract.

Rather than look backwards at recreating the “old normal,” the focus needs to be on how to turn previous negatives into positives in the “new normal.” An example could be an application of the thinking espoused by two New Zealand scientists, Matt Boyd and Nick Wilson, whereby in a post-pandemic climate, a country’s isolation and ability to protect itself from future pandemics can turn a historic disadvantage into a unique selling point.

In opening economies whilst learning to live with COVID-19, Governor Antoine recently identified four key areas on which to focus:

- Expand Connectivity – an imperative for the future being to stay connected and connect the unconnected.

- Adopt a Growth Mindset – learn from problems and reframe problems into opportunities.

- Manage Finances Wisely – it is a marathon not a sprint, so identify essential and non-essential spending, focusing on needs, not wants.

- Support Regional Solidarity – “because many large countries are so pre-occupied with their own issues, they do not have too much time for small states like us. So, we have to take care of our own business. And an important part of that is standing together, sticking together in this moment of adversity; regional solidarity is crucial.”

The attitude of international organizations and the ability of small nations to band together to ensure their collective voice and needs are heard, understood and addressed, will be crucial.

Albert Einstein once said, “In the midst of every crisis lies great opportunity.” For the Isle of Man and all other small countries, the focus, extremely difficult but vital, must be on identifying and acting upon such opportunities.

*****

Mark Shimmin MBE is the Executive Director of the Small Countries Financial Management Centre. Prior to taking up that role in 2014, he had served over 10 years as the Chief Financial Officer (equivalent of Permanent Secretary) in the Isle of Man Treasury, the Government department responsible for direct and indirect taxation, economic affairs, financial services promotion, and Information Technology.

This article was written as part of the Addressing Global Crisis Project (AGC), which is run by the University of Central Florida’s Office of Global Perspectives & International Initiatives (GPII). AGC examines how governments, individually and collectively, deal with pandemics, natural disasters, ecological challenges, and climate change. AGC is organized around five primary pillars: (1) delivery of services and infrastructure; (2) water-energy-food security; (2) governance and politics; (4) economic development; and, (5) national security. Through its global network, AGC facilitates expert discussion and features articles, publications and online content.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of The Small Countries Financial Management Centre.